The Many Faces of Book Covers

The cover is the face of the book. It gives insight into what you can expect from the content. Like people, book covers also have many different faces. When a book gets translated into other languages, the cover often goes through a similar process. Based on where in the world it gets published, the translated book cover can look very different from the original one. Why is this often the case?

Sometimes, the case is simply that when international publishers buy the rights for the book, it often does not include the cover (John August, 2018). It is way easier for them to make their own covers, than having to license the original one from the publishers. However, often, it can be because different countries have different tastes and styles.

As mentioned in my previous post, book covers are marketing tools, made to increase the sales of the book. Therefore, if an international publisher buys translation rights for a book, they have to make sure that the cover will appeal to the audience in that country. It all depends on their culture and what the market prefers. This is why the covers of the translated books often say more about the country it is published in, than the country of origin (Alvstad, 2012, p. 79).

To give an example, US publishers often go for more literal interpretations on book covers, whilst UK publishers have been known to experiment with more abstract cover designs (Kean, 2017). Certain features, elements or designs are just more acknowledged or preferred in some countries than others.

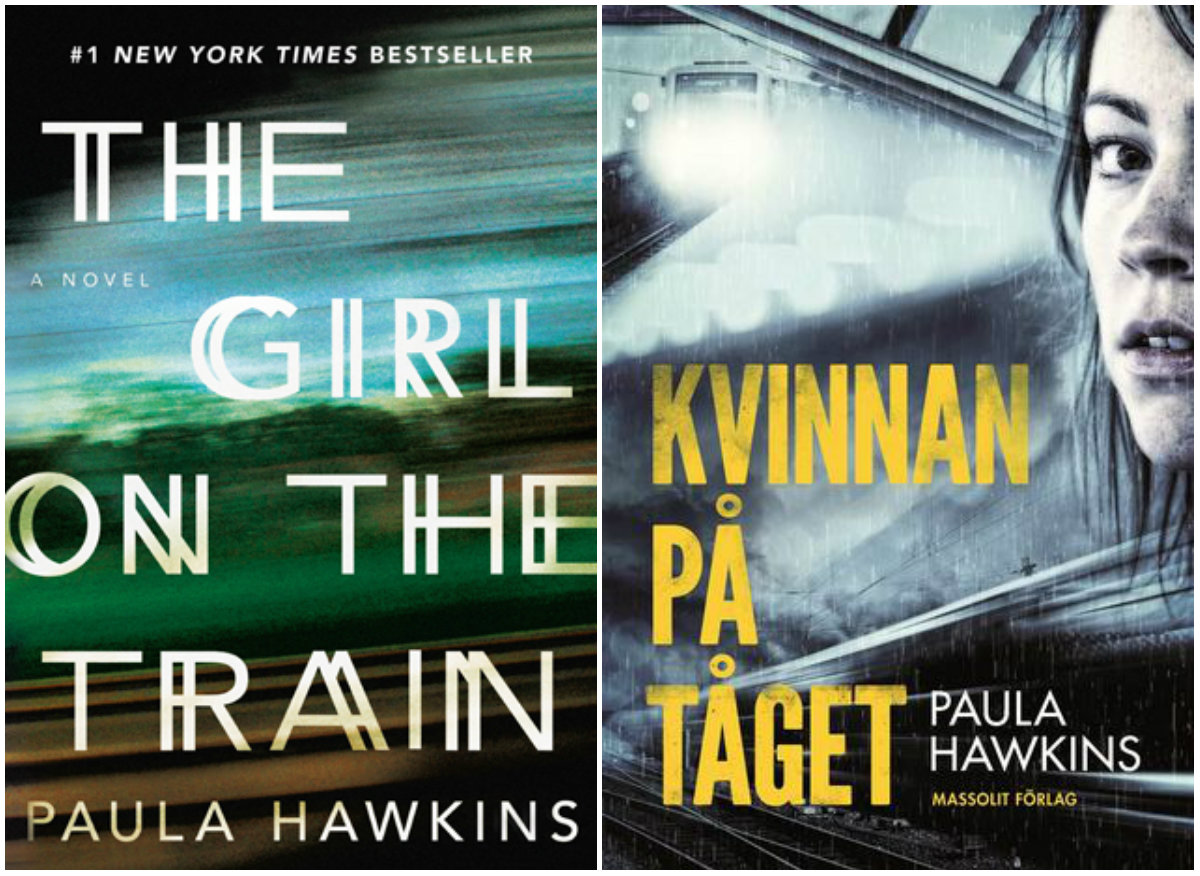

This is for instance the case on the covers of The girl on the train by Paula Hawkins. The first cover is the US edition, whilst the second is the Swedish one. Both covers look somewhat similar, with the distinct dark colour that usually characterises thrillers. But, the designers have chosen different paratextual elements to emphasise. For example, the author’s name on the US edition is larger than on the Swedish. This is often the case if an author is more known in the country of origin (or other countries) than the translated one. As the audience might not know who the author is, the name might not be as emphasised as it will not be the main selling point.

Left: US edition by Riverhead Books (2015, Retrieved from: Goodreads.com) Right: Swedish edition by Massolit Förlag (2015, Retrieved from: Goodreads.com)

Sometimes, book covers of translations end up being misrepresentative or unsuccessful. These are either unfaithful to the book’s content, or represents stereotypical depictions or conceptions. The reasoning for this, is that often it is the norms or values specific to a culture that has a large impact on the appearances of the translated books (Kung, 2013, p. 55). But initially, it is the publisher or designer that acts as the mediator between the book and the readers.

Whether the translated cover is consistent with the book or not, one thing is certain. They have an immense effect on the readers’ interpretations of the content. As Marco Sonzogni (2011) says:

‘Every different design confers a new identity of the book, changing the point of view and providing a new (and sometimes even alternative) entry into the narrative.’ (p. 25)

If the cover goes too far from the actual content, it can give a wrong impression of the story and lead to disappointment. However, there is a divide in opinions on the topic of representation. Is there a rule that book covers must represent the original story?

Some think so. On the one hand of the argument, there are the people that say that the translation should always stay somewhat true to the original, to convey the “gist” of the story. On the other, the argument is that translations (and also covers) are freestanding from the original (Mossop, 2017, p. 11).

Which side are you on?

References:

Alvstad, C. (2012) ‘The strategic moves of paratexts: World literature through Swedish eyes.’ Translation Studies, 5(1), p. 79

Goodreads.com. (n.d.) Kvinnan På Tåget. [online] Available at: <https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23377235-kvinnan-p-t-get> [Accessed 29 April 2020].

Goodreads.com. (n.d.) The Girl on the Train [online] Available at: <https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22557272-the-girl-on-the-train?from_search=true> [Accessed 29 April 2020].

John August, (2018) ‘Why International Book Covers Are So Different.’ [online] Available at: <https://johnaugust.com/2018/youd-hardly-recognize-arlo-finch-overseas> [Accessed 28 April 2020].

Kean, D. (2017) ‘Cover Versions: Why Are UK and US Book Jackets Often So Different?’ [online] the Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/sep/26/cover-versions-why-are-uk- and-us-book-jackets-often-so-different> [Accessed 29 April 2020].

Kung, S. (2013) Paratext, an alternative in boundary crossing: A complementary approach to translation analysis. In: V. Pellatt, ed., Text, extratext, metatext and paratext in translation, 1st ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing, p. 55.

Mossop, B. (2017) ‘Judging a translation by its cover.’ The Translator, 24(1), p. 11.

Sonzogni, M. (2011) Re-covered rose: a case study in book cover design as intersemiotic translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, p. 25.